The current data economy is based on apathetic approval – everyone clicking on “I accept the terms and conditions” without reading them, let alone bargaining for better terms and conditions. However, MIT professor Alex Pentland has spearheaded a small movement with another idea on how things could work. Pentland is one of the most-cited computer scientists globally and played a key role in the introduction of GDPR, an EU regulation dubbed the “greatest shake-up of the privacy legislation in more than 20 years”. According to Alex, the answer lies in cooperative ownership of data, and the force best positioned to bring this change is the credit union movement. The first chapter of this article seeks to describe the vision laid out by Pentland and his colleagues at MIT, while the second chapter provides some new ideas on how it could foster a further shift towards an economic system where cooperatives would play a more prominent part.

Pentlands’ vision for credit unions

Credit unions are not conventional corporations, they are consumer-owned cooperative banks. This means that they are fully owned by their members, in this case, ordinary customers who save or borrow money through the credit union. The profits are distributed to the members, who also elect the board of directors on a one-member-one-vote basis. The popularity of credit unions has been booming for generations, growing from 6 million in the late 1960s to 120 million members by 2019 in the US.

In Pentland’s vision, credit unions would offer their members an opportunity to join a “data cooperative” where you would pool data together with others to collectively bargain for better terms and conditions on how your data is used. He explains:

“What we discovered, and I have a bunch of lawyers that are part of my group, is that there are certain sorts of cooperatives which are licensed by law, to manage peoples’ data. Just by accident in the US, credit unions are licensed to handle your digital data, which is basically everything about you. They can act as your legal representatives. They don’t own your data, they host it. They could for instance, and we built software for this, have you just check a little box, and your credit union would download all your data.”

“…it is practically possible to automatically record and organize all the data that citizens knowingly or unknowingly give to companies and the government, and to store these data in credit union vaults. In addition, almost all credit unions already manage their accounts through regional associations that use common software, so widespread deployment of data cooperative capabilities could become surprisingly quick and easy.

While a usual customer might not notice much difference from a conventional bank, except the slightly better rates, credit unions differ from corporations in fundamental ways due to being cooperative legal entities. This has implications when it comes to matters like customer data because credit unions have a legally binding fiduciary duty to protect the rights and act in the interest of their members instead of investors whose interests might differ from those of customers.

Existing technology would easily enable credit union members to download software on their phones and laptops that would request all the data extracted from them and have it stored in a personal data storage or a “vault”. Credit unions could also help members grow their vault by requesting other information collected from them to be stored in their vaults. The example Pentland uses is that of medical information. In the US, everyone has legal rights to their medical information, but hospitals often make it difficult to obtain. It would be easier to obtain it by joining a data cooperative that would request the information on behalf of many members, instead of having each individual member go through the process separately.

The pooling of data also makes it more valuable. It is not very valuable for an individual member to know how much cat food they buy. But pool data together with others, and the credit union could enable all members who regularly purchase cat food to do so collectively and bargain a lower price. Pentland sees this sort of collective bargaining for “bundled offers” as one of the key tangible economic benefits data cooperatives could provide to attract credit union members to join.

Alongside these sort of tangible economic benefits that the credit unions could now provide, there would be a more profound change towards a more ethical way of analysing data. This would happen through “Open Algorithms” or OPALs, a set of requirements defined in MIT to vet algorithms. The most important part of the requirements is that the data is never moved or copied from the vault and “algorithms are moved to the data” instead. The current norm is the opposite – collecting a lot of data into one location where algorithms are run on it. Instead, with OPAL each personal data vault runs the algorithm independently, and together they return an answer aggregated in a way that does not risk the privacy of any member.

To illustrate the difference between the typical algorithms and OPAL, let’s imagine a chef wanting to start a Greek restaurant. The status quo resembles the chef buying the names and addresses of everyone in the state and running an algorithm to see how many people with Greek last names live in each area to help find an ideal location for the restaurant. With OPAL, the chef gets the information on how prominent Greek last names are by area, as the algorithm that detects connections between Greek last names and home addresses is run separately on each person’s data vault. However, the chef doesn’t get to know the names and addresses of people. OPAL allows answers to specific questions the algorithms ask, but not access to the raw data that the insights are extracted from. Instead of obtaining your data and doing whatever they want with it, businesses get general answers by asking specific questions through algorithms that are automatically vetted by the data cooperative to ensure adherence to OPAL requirements.

Of course, the reality does not resemble such a situation. In reality, data is hoarded by the few giants that control access to it. Indeed, Pentland sees data cooperatives as a solution to the “cold start” problem of incumbents possessing a massive advantage over new competitors in the form of hoarded data.

Alongside this, people could change the settings of their personal data easily. The credit union network could run an OPAL algorithm to detect if there are many credit union members who donate to Wikipedia and offer them a possibility to only share data to research conducted by universities that encourage and enable their students to improve Wikipedia as part of their education. Wikipedia reaches a massive audience during their fundraising campaigns. In these campaigns, they could encourage their readers to join a data cooperative to bargain for more Wikipedia friendly practices at universities that use their data. This could reach more credit union members than the most expensive advertising campaigns in the sector while helping Wikipedia form mutually beneficial relationships with universities.

It is also worth noting that it would require little effort and time to scale rapidly. Pentland explains:

“It is technically and legally straightforward to have credit unions hold copies of all their members’ data, to safeguard their rights, represent them in negotiating how their data is used, to alert them to how they are being surveilled, and to audit the companies using their members’ data. The power of 100 million US consumers who are practically and legally in control of their data would be a force to be reckoned with by all organizations that use citizen data and would be one very decisive way to hold these organizations accountable. The same potential for credit unions to balance today’s data monoliths exists in most countries around the world.”

He mentions a discussion he had with a leading data management software provider for the entire credit union sector, stating that he “will add some of our special magic to all the credit unions without them knowing” and explains that, from the credit unions perspective, they will continue running software like usual without even noticing a new update that enables giving members more choice over their data. It is a sign of historical and structural forces at play when, without their conscious intention and effort, the credit union movement almost accidentally happens to possess legal, economic, and technological structures that put it in an ideal position to enable people to own their own data in a more meaningful manner.

As Pentland states:

“From a software point of view, we’re there. From a legal point of view, we’re there… We just need a couple of examples to demonstrate exactly how this works.”

Helping Members Help Each Other

If I, as a customer member of many old and big cooperatives, would like the people working in them to read one article, it would no doubt be Nathan Schneider’s Co-ops, from Lateral to Vertical and Back Again. And if there was one sentence I would hope they would ask themselves every day that perfectly encapsulates the simple but so profound idea of the article, it would be the following:

“Co-ops of the near future could find themselves asking less what they can do for their members and more what their members—and potential members—can do for each other“.

An example Schneider gives comes from one of the earliest North American credit unions, Desjardins, that has grown to include a large majority of Quebecers as its members: “the secret was having parish-level groups of members who knew each other evaluating loan applications. Through long-standing relationships, members could determine creditworthiness in communities where conventional banks couldn’t tell a follow-through-er from a cheat.”

A correct but backward-looking view among credit unions is to say, “well back in the day, it was useful for members to know about each other to help evaluate whether a loan is paid back, but now we have so much other data that it doesn’t matter that much anymore”. And there’s research indicating that credit unions have more “soft information” (which most people would call “knowing your customers personally”) but that soft information doesn’t give as much advantage as before.

Even though correct, what makes this response backward-looking is that it doesn’t look into new ways to utilise this difference. The legacy of all the good people who could help their customers better than banks have earned the movement greater trust throughout the country, which can be turned into a competitive advantage if people trust their credit union with their data more than conventional corporations.

Data cooperatives should be utilised to foster new ways of member-to-member mutual support. This could happen through members forming cooperatives and other mutual aid networks through which they provide goods and services to each other. In the previous chapter, I described how data cooperatives could be used to enable 10 members who buy a chainsaw to bargain a discount through a bulk purchase of 10 chainsaws. But we could go one step further – for example, we could help members form a cooperative where they buy one good chainsaw, and share it, instead of having 10 lower quality chainsaws that are only seldom used. Gradually it could be expanded into a larger tool-sharing cooperative, where members don’t have to buy a $100 chainsaw or a drill; they can simply pay a deposit of $200, lend a chainsaw or a drill worth $200 from the cooperative, and get their money back once they return it unharmed, with some payment to compensate for the administrative costs and natural depreciation.

Cooperative models better enable businesses based on “I scratch your back, you scratch mine” reciprocal type relationships. While the entire economy cannot be run through these kinds of relationships alone, technology makes it possible to expand it into areas where it was not practical before.

So what could this reciprocity look like in practice? Let’s imagine that through a data cooperative, credit union members who bulk-purchase cat food would be asked if they would mind having another member’s cat in their house for a week per year, if, in return, they could place their cat to another member’s care for a week for free. If a business for cat-sitting is formed as a typical start-up, the incentive is to make you pay as much as possible for someone to watch your cat and someone else pay you to watch theirs, with your share of the pay as small as possible. The goal is to take as much of a commission from transactions as possible without losing the customer, and due to network effects creating a lack of competitors, the customers might have little choice when trying to change to a competitor with better rates.

If the cat-owners form a cooperative for this purpose, the incentive is to minimise the costs to the members with the end goal of zero costs – you take care of my cat, I take care of yours, no financial transaction takes place. If there is no transaction of money, that would be catastrophic to a conventional company, as it would also mean zero commission. Instead of scaling up to dominate the market and charge higher commissions, cooperative scaling enables one to lower their costs closer to zero as the cost of maintenance per user is lowered. In this race to zero, credit unions and data cooperatives can be of great help. Let’s imagine the credit union is already collectively bargaining for better deals on cat food and pet insurance for their members. They could help negotiate an adjustment to their pet insurances, allowing them to insure their pets when taken care of by another member. They could also automatically organise the cat food purchases to be delivered to a different address when the cat is temporarily staying at that address. For a tool-sharing cooperative, instead of the founders building and getting people to use software to manage deposits when lending the tools, the credit union could help enable that through their existing website and mobile banking app. It could also help credit union members who take home-improvement loans to lower the costs of the equipment required to do the improvements they are working on.

Another way to cover these costs is to channel a proportion of charitable donations to help these new cooperatives. In the US, there is only one accelerator program for cooperative start-ups, Start.Coop. It was established in 2019 and provided 8 start-ups a $10,000 no-strings-attached grant and mentoring. The cooperatives have already made history in a short period of time – one of the ventures became the first cooperative in the US ever to receive venture capital investment, and another became the first worker cooperative in the country to buy a conventional company and convert it into worker ownership. One of the ventures that is especially relevant for data cooperatives is the Driver’s Seat Data Cooperative, which enables people like Uber drivers to collect their data and use it for their own benefit, such as by coordinating when and where to drive to maximise their pay. The cooperatives that become successful also have to commit to donating a small share of their surplus back into the accelerator to fund future cooperatives. The Start Coop is already funded by other cooperatives, spearheaded by CCA Global Partners, a large cooperative of many small independent carpet flooring businesses doing bulk-purchasing to acquire the scale needed to compete with bigger companies.

The US credit unions have $56 billion in excess capital. This is around $4800 per member. If only $1 out of the $4800 would be used to fund Start Coop, it could provide a $10,000 grant to 12,000 cooperative start-ups instead of 8. Credit unions already give a lot to charitable causes; if some of those charitable donations would be directed to help members help themselves by forming cooperatives, it would cost the members nothing, since they would have otherwise given it away.

In fact, it could produce economic value for them if instead of giving grants, credit unions would provide investment into the cooperatives. In 8 states, credit unions are allowed to make equity investments into cooperatives, but so far only the Vermont State Employees Credit Union does. The program has been a success, providing VSECU with returns on their investment alongside helping shape the local economy towards a more equitable direction where ownership of businesses is more widespread and democratic. Replicating this in more credit unions that are based in the 8 states where it’s allowed while lobbying for more states to allow it could unleash massive amounts of capital flowing into new cooperative start-ups, starting a boom that would reprogram how American businesses are owned and governed.

How to get there?

The legislation and technology required to make these visions into a reality already exist. The only thing needed now is organising people to use these tools to build this new world. It’s my belief that what is needed is a ground-up mobilisation of ordinary credit union members to exercise their democratic powers within these institutions to campaign for democratising data ownership. This can mean standing for their board of directors or attending the annual general meetings to put forward resolutions. There are countless credit unions that are more than open, often even desperate, to find members willing to volunteer to serve on the board of directors, and often the annual general meetings are attended by a small group of people, meaning that it would require a relatively small number of people and little effort to wield power through these massive, underutilised democratic mechanisms.

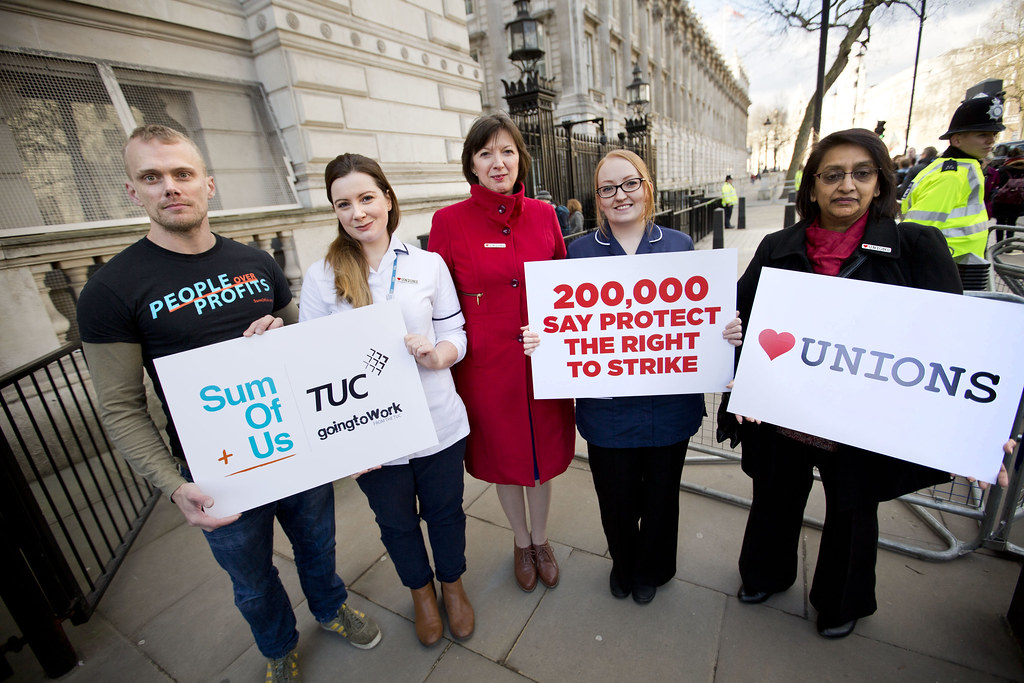

This is why me and Iwan Doherty (my fellow editor of Mutual Interest, the publication you are reading right now) have established a global network called Members For Cooperation. We want to organize rank-and-file members of big and old cooperatives to turn these old giants’ attention into supporting new cooperatives. Our first campaign focused on the UK, but we are planning to start organizing US credit union members soon, and one of the key goals is campaigning for the adoption of the data cooperative model. You can join Members For Cooperation by signing up to our email list here. Before subscribing, there is a questionnaire that allows you to tell us which credit union you are a member of and how you would be interested in helping out. Do mention if you would like your credit union to help democratize the ownership of data.

These ideas might sound radical or utopian because they would lead to a profound change in how the world’s most valuable asset is owned. But the beauty lies in the fact that it would require very little to spark the implementation of these ideas. There are 125 million members spread across 5000 credit unions in the US – a single member volunteering to serve in the board of their credit union that manages to convince the rest of the board to adopt this model of data democracy would be enough to topple the first domino. From there it could rapidly be replicated on a massive scale, changing the entire trajectory of the economic system. The data economy could be turned from a force that suppresses democracy into a force that fosters it. It could turn internet users like me and you from products that are being sold into owners of the value we create.

Mutual Interest Co-operative is democratically owned by our readers and writers.

We are not owned by billionaires or governments.

Mutual Interest Cooperative is democratically owned by our readers and writers.

We are not owned by billionaires or governments.